Buy this book. Peshtigo 1871: Peter Pernin’s Peshtigo Fire Memoir The Finger of God Is There! TBR Books New York 2021.

Your book is a fresh English translation of Peter Pernin’s 1874 French memoir, Le doigt de Dieu est là, a Peshtigo Fire survivor’s account. One very interesting thing about you is that, as stated by Mary Norris in the Praise part of your book, you are the great-great-grand nephew of Father Peter Pernin, who was a French missionary in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Could you let us know how you ended up knowing about this illustrious heritage? And what made you so interested in translating this book at this stage of your life?

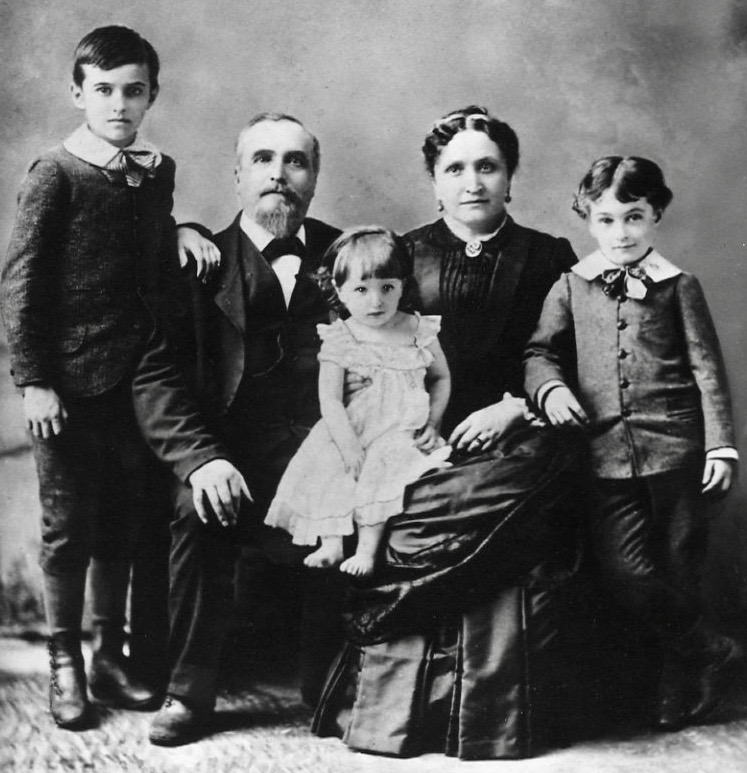

My father’s mother, Zoé Lassagne Mercier (1883-1969), whose parents emigrated from Bagnols-sur-Cèze (Gard) and Lyon, grew up in the French community of Chicago. When she lost those parents as a young teen, she boarded during the school year and spent summers with relatives, every August with Father Peter Pernin, then in Minnesota, who was her mother’s uncle. Pernin was a father figure to her and her best friend until his death in 1909. The fond feeling she had for her grand uncle came down to me through my father and his siblings when they would talk, in legendary terms, about his heroism during the Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871. Jean-Pierre Pernin (1822-1909) was a French missionary priest from Flacey-en-Bresse (Saône-et-Loire) and Catholic pastor of Peshtigo at that time.

When I discovered ten years ago in the family archives the carte de visite that Pernin had made in St. Louis within months of having survived the fire (published in my book on page 30), I realized I had a way into a story that had never been told.

I am a PhD in Classics and a professor of Greek and Latin language and literature at a Catholic seminary and had previously translated from Latin a comedy of Terence, Brothers (1998). It was natural for me to want to put the story of Pernin’s life on a solid documentary foundation and present his writing in an accurate, critical way. Teaching Classics in a Catholic seminary itself gave me insight into Pernin’s personality. It was his Classical studies in seminary in the 1840s at Meximieux (Ain) that made him a writer.

Academic interest in French missionaries in America has been lively: two recent outstanding examples are Michael Pasquier Fathers on the Frontier: French Missionaries and the Roman Catholic Priesthood in the United States, 1789-1870 (Oxford 2010) and Tangi Villerbu Les missions du Minnesota : Catholicisme et colonisation dans l’Ouest américain, 1830-1860 (Rennes 2014). What began as a work of family history and deepened the more I read is what I hope now is a small contribution to American religious history.

To what extent does this book represent a must read for North American French literature and culture? What makes this book so unique for anyone interested in American French literature? We know a lot about Louisiana French literature, but what about the Wisconsin French literature? Any major French authors from Wisconsin anyone should be aware of? Could you tell us more about that?

The popularity of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s three partial editions of the 1874 English translation (1919, 1971, 1999) has entirely obscured that Doigt de Dieu was written in French. The French original has never been republished before this.

In that sense, I am bringing to light a new piece of North American francophone literature.

John Ireland, Catholic archbishop of St. Paul, Minnesota (1838-1918), an ardent francophile, graduate of the same Collège de Meximieux as Pernin, made a point of bringing French missionary priests to Minnesota. Pernin’s publishers in Montreal, Eusèbe Senécal and John Lovell, published a number of 19th century French missionary memoirs. But Pernin’s memoir has now gone through four editions, remains a well-known work of Wisconsin history, and was cited three times in the 2010s by writers of environmental history. Can your readers suggest other 19th century North American French works that have had similar impact in the United States?

Could you let us know what difficulties you have faced when translating the original book? Any technical difficulties regarding the language itself? Obscure references you have encountered? Translation issues?

Some examples:

- should I keep a phrase in French or not? For Pernin’s, “Je ne pus trouver qu’un pantalon grossier d’une couleur jaunâtre que les manœuvres portent pour travailler dans les moulins à scie. Je le pris, faute de mieux… (61),” I translated, “I could find only the coarse, khaki pants laborers wear to work in the sawmills. I took them faute de mieux…” instead of “for lack of anything better,” thinking, well, he’s French. For “comme si la chaleur l’eut consumé à l’étouffée (65),” I translated “as if the heat had cooked [the linen I had buried] à l’étouffée,” thinking it an allusion to Bressane chicken cookery.

- When at the riverbank Pernin’s neighbor was annoyed to be pushed into the water for his own good, Pernin advised “il valait mieux se mouiller que de brûler. (46)” I translated, “it was better to moisten than to burn,” trying to catch the playful allusion to 1Corinthians 7.9: “it is better to marry than to burn (il vaut mieux se marier que de brûler).”

- I translated “je m’avance plus ou moins loin en faisant la chasse aux faisans (14)” as “I go on a fair distance pleasantly hunting pheasant,” trying to catch the pun.

- As in “je m’avance,” Pernin often uses the present tense for vivid narration of an event in the past, a technique familiar from Classical Latin writers called historical present. This is a mannered influence of his Classical reading and I kept it in the French text and the translation against the advice of those who told me, you can’t use the historical present!

- There was one crux I did not solve: “courut jusqu’au †2e magasin† et y déposant son panier sur le seuil de la porte (39).” Pernin’s housekeeper after collecting a basket of valuables, in panic “ran as far as the †second store† and dropped her basket off at the doorstep.” The 1874 Lovell translation supplies “neighboring store.”

Dr. Tessa Nunn pointed out to me that un magasin can also describe a trunk attached to carriages for storing luggage, chests, and packages.

The definition from the Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales is: “sorte de panier ou de coffre attaché à l’arrière des diligences ou coches et servant à mettre les malles et colis des voyageurs à l’abri de la pluie et de la poussière.” Perhaps I should have accepted this and translated, ‘she ran as far as the second trunk,’ but even so it remains a crux.

Two examples of why a completely new translation was necessary:

- “Pendant que je passais à Terre Haute (Indiana) (87)” in the 1874 Lovell translation became “Whilst passing through Indiana on my way to St. Louis…” The Canadian translator was evidently unaware that Terre Haute is a place name. When you recover Terre Haute, it is then easy to discover from contemporary newspapers what the lecture was that Pernin stopped to attend — “Great Fires of the World and Their Results,” December 15, by Rev. John L. Gay, rector of St. James Episcopal, Vincennes, Indiana — and thereby to add an episode to an account of the influence of Protestant theology on a Catholic missionary.

- Pernin loved his horse as good friend (66). He went out of his way to identify his horse’s remains after the fire: “Son corps était enflé sous l’effet de la chaleur ; son flanc éclaté laissait sortir une partie de ses entrailles qui étaient rôties. (65)” The 1874 Lovell translation euphemizes these gory details, but it is true to friendship, as painful as it is, to know precisely a loved one’s cause of death.

Was it difficult to find a publisher for such a book?

I was fortunate to connect with Fabrice Jaumont, president of the Center for the Advancement of Languages, Education, and Communities, a nonprofit organization that promotes multilingualism, cross-cultural understanding, and the empowerment of linguistic communities.

Fabrice, based in New York, serves as Education Attaché for the Embassy of France to the United States and is the author of The Bilingual Revolution: The Future of Education is in Two Languages (2017). TBR Books is CALEC’s publishing arm.

A book about a work originally published bilingually in French and English in 1874 that opens many questions of French and American cultural interaction was a good fit.

Could you elaborate on this fascinating transition from a French-based catholic culture experienced by Pernin to a more American-Calvinist – but still Catholic – approach? Is there anything pertaining to the role of Catholicism within the French communities of America we can learn through this book?

If God exists, why does God allow evil? That question will always challenge and various religious traditions and varieties of theology within Christianity have answered it differently. Traditionally, Catholicism emphasized personal effort under the sovereignty of God: “God’s providence does not exclude contingency.” (Aquinas); ”Pray as if everything depended on God and work as if everything depended on you.” (attributed to Ignatius of Loyola). Calvin by contrast emphasized God’s all-power: “all prosperity has its source in the blessing of God, all adversity is his curse.” I suggested in the book that Pernin’s interpretation of the Peshtigo fire as God’s punishment on a guilty creation was influenced by American Protestant thought.

I hope to provoke interest in further study of Protestant influence on Catholic missionary priests in the 19th century.

Pernin seems most a French Catholic in his readiness to believe in miracles: an apparition of the Virgin Mary, the preservation of his tabernacle the night of the fire, and the survival of the Shrine of Notre Dame de Bon Secours, which the fire bypassed. He was devoted to Our Lady of Lourdes, an apparition that had taken place recently, in 1858, and was proud to have dedicated the first church in the United States to Our Lady of Lourdes when he rebuilt the Catholic church in Marinette, Wisconsin in 1874. He would have known about the “Hosties miraculeuses” at the Abbey of Faverney in 1608, officially recognized by Catholic authority recently, in 1864.

You mention in your book the French Belgian community pastored by Pernin. Could you elaborate on that? It’s quite interesting to understand through your account that it seems there is a subtle difference between French and French-Belgian communities.

The Belgian population that Pernin knew in Wisconsin faced terrible poverty and economic hardship unlike that of other French-speaking immigrants to Illinois.

Driven particularly by the effects of the northern European potato blight, in waves in 1847-9 and again in 1853-6, some 15,000 Belgians had emigrated over 15 years and established communities in, among other places, Indiana, Illinois, and, most populously, Wisconsin.

The Belgian emigration to the Door Peninsula east of Green Bay, Wisconsin became the largest community of Belgians in the United States.

Edouard Daems, a Crosier priest from Flemish Brabant and a figure foundational to the diocese of Green Bay, is credited with bringing Belgians to the area that became known as Aux premiers Belges.

When Philibert Crud (1828-1913), a French missionary from Saint-Étienne-sur-Chalaronne (Ain), who became Pernin’s best friend in America, arrived in 1864 at the rectory of Robinsonville (now Champion), Wisconsin, as he told Antonin Voyé in L’Abbé Crud et la nouvelle orthopédie (1912), Belgian settlers emerged from the forest to greet him, “poor, ragged, dressed in clothes impossible to describe.”

Quand M. Crud arriva au presbytère de Robinsonville, il fut salué par les volées joyeuses d’une cloche suspendue à quatre poteaux, c’était le clocher. Il vit déboucher de tous les points de la forêt, pauvres, déguenillés et dans des costumes qu’il est impossible de décrire, des groupes nombreux de paysans. Ils venaient, à l’appel de la cloche, voir le missionnaire qui leur avait été annoncé.

They lacked basics; they lived in miserable cabins together with their animals. “Their cleared land had begun to give potatoes and wheat, but without roads it was impossible to get them to market. They had an abundance of the most beautiful fir trees in the world, but no horses to transport them.”

Les premières années avaient été dures ; dans une propriété qui en Europe les aurait enrichis, ils manquaient des choses les plus utiles. Leurs maisons n’étaient que de misérables cabanes où ils vivaient parmi leurs animaux. Les terres défrichées commençaient à donner des pommes de terre et du blé, mais, en l’absence de tout chemin, il était impossible de les vendre; ils avaient en abondance les plus beaux sapins du monde, mais pas de chevaux pour les transporter.

The Belgian consul in Chicago, Adolphe Poncelet, who bought land in Illinois and Wisconsin and brokered it for incoming Belgians, reported after visiting the Door Peninsula in September 1855 that Belgian colonists had been misled as to the value of their land. Francophone emigrants to Chicago from Quebec, France, and Belgium could join an urban economy. Those who became farmers in downstate Illinois prairies found that the sod, however tough, was easier to clear for new farmsteads than the Wisconsin forests of fir and maple. And Wisconsin timber did not have the same value as it would have in deforested Europe or with the coming of industrialized logging in the late 1860-70s.

The original French title is Le doigt de Dieu est là! Ou Episode émouvant d’un évènement étrange, raconté par un témoin oculaire, which gives the book a very religious tone. What has been the reception of this book throughout the XXth century in academic circles? Is it very well-known within French and Religious studies? Could you also let us know the role played by Adele Brice, and what happened at the National Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help during the Peshtigo Fire?

When the Wisconsin Historical Society in 1918-19 first partially reprinted the 1874 English translation of Pernin’s book in the Wisconsin Magazine of History, the editor Joseph Schafer decided to leave out the parts “dealing largely with matters of Catholic faith” and pertaining “to the religious reflections and ideas of the author.” That decision also informed the editions of 1971 and 1999.

So, while Pernin is a vivid witness to the Fire and writers on forest ecology and environment continue to cite Pernin in the Wisconsin version for his evidence on deforestation

That is what I hope to remedy with my edition! For all its importance as evidence for the Great Peshtigo Fire, Doigt de Dieu was written primarily as a work of theology and theodicy, justifying the ways of God to humanity, and should take its place as a work of North American francophone literature that concerns missionary and religious studies.

the book has been utterly unknown to students of North American French literature, religious history, or even of Marian apparitions and visionaries.

Adèle Brice (1831-1896) emigrated to a farm on the Door Peninsula with her Belgian family in 1855. She experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary in 1859 and in response established a religious community, catechetical school, and a Shrine of Notre Dame de Bon Secours in Robinsonville (now Champion), Wisconsin. Pernin knew her first when he was pastor of Robinsonville in 1868-69. When the fires of October 8-9, 1871 destroyed much of the east side of Green Bay as well as Peshtigo, the Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help in Robinsonville — chapel, convent, and school on the site of the Virgin Mary’s appearance to Adèle — should also have burned. But the fire passed it by with great precision and this was taken to be miraculous. Pernin’s is the first witness to this Mariophany, the first in the United States to receive official Catholic approval, and to the claimed fire miracle, which seemed to vindicate the truth of the apparition, events in both Catholic history and Wisconsin lore.

Was anyone else involved in the editing of this work that you would like to thank?

Archival research made it possible for me to tell Pernin’s life story for the first time, so I am especially grateful to the archivists and librarians who opened their treasures.

Green Bay diocesan archivist Olivia Wendt allowed me to publish in its entirety a letter important to the history of the Shrine of Good Help.

In the Saône-et-Loire departmental archives in Mâcon I saw some of Pernin’s parish assignments reported by the diocese of Autun to the government in “État Des Mutations survenues parmi les vicaires de paroisse.” The diocesan archives of Quebec and Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière hold poignant letters back home from 19th century missionary priests in Illinois.

Many French departments have now digitized their 19th century Actes d’État Civil.

This makes easy (once you figure out how to read the handwriting!) family and social history research that used to take much time and travel. Here, for example, is a link to the civil birth record of Jean-Pierre Pernin, Flacey-en-Bresse (Saône-et-Loire), February 24, 1822, dated May 13, on page 108. (The preponderance of contradictory evidence, however, supports February 22 as his birthday.)

Last week I was in Peshtigo to take part in the 150th anniversary observances of the Great Peshtigo Fire held by the town and the Peshtigo Fire Museum. As I listened to the Father Pernin re-enactor use my research to explain Pernin’s life to visitors at the Museum, I was happy to think back to the day I discovered this or that fact of his life in archives.

What have been the first feedbacks you received after finishing your translation?

Environmental historian Stephen Pyne reviewed the book for International Journal of Wildland Fire.

In the book I critique what I take to be Pernin’s Calvinist view that the Peshtigo disaster was God’s fire and brimstone on a sinful city. Peshtigo, a town of saloons and brothels accommodating lumbermen on the frontier of the Wisconsin logging boom, to Pernin was “the modern Sodom meant to serve as an example to all. (90)”

Pyne himself in another context identified the real causes of the Peshtigo fire: “a prolonged drought, a rural agriculture based on burning, railroads that cast sparks to all sides, a landscape stuffed with slash and debris from logging, a city built largely of forest materials, the catalytic passage of a dry cold front…” And I noted Catholic developments in the theology of God’s mercy: pace Pernin, God in Catholic understanding is not an Avenger; wild fires have a God-given purpose in God’s creation.

But Pyne ended his review with a memorable epigram: “the Anthropocene also has its Sodoms.” That is to say, God may be merciful, but nature is not. Abuse of the environment causes disaster and we, not God, are responsible.

As the covid pandemic lingers, our climate changes, and wildfires continue to burn in North America, Pernin’s Doigt de Dieu invites us to ponder many questions: is God, if God exists, a merciful or vengeful God? to what degree are human beings free and responsible under divine sovereignty?